Research and Publications

that support the strategies used in

Living Well: Less Stress, Better Health and More Love

DeLoughry T. and K. DeLoughry (1983) Steps to Manage Stress in Help Patients to Better Breathing New York: American Lung Association

The Satisfaction Skills that Kathy and I developed for teens at Buffalo Children’s Hospital (see “Like Getting Stoned” ) were well received as a component of “Help Patients to Better Breathing, published as the American Lung Association’s national programs for emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

DeLoughry, T. (1990). The Influence of occupational stressors and psychosocial factors on participation in a stress management workshop. State University of New York at Buffalo.

My doctoral dissertation, which studied 540 employees in three different workplaces, found that social support (i.e., “other people who are important to me think I should participate”) was significantly more important than having a high level of stress in predicting who would attend worksite stress management programs.

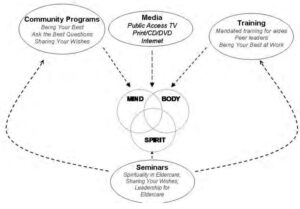

These finding have influenced much of my work, including Caring Teams (Illustrated below) which was funded by a grant from the Ralph C. Wilson Foundation..

DeLoughry T. (1994) Feeling Fit: Preventing Illness and Improving Quality Medical Interface September ,109-114

We focused on the “social support” findings from my dissertation (see above) by engaging middle school teachers, students and family in a “whole school” wellness programs in forty-six school districts with grants from New York State United Teacher and a Drug Free Schools grant from the NYS Health Department, as well as support from a large managed care organization where I directed wellness and disease management programs.

We then used the same materials (e.g., a booklet and a family progress refrigerator chart) to conduct worksite wellness program, as well as primary care programs to prevent and control chronic illness. Our team’s efforts were honored with a national Award for Excellence in Quality Improvement from the American Managed Care Review Association

DeLoughry, T. (2008) “Spirituality and Eldercare” in Spiritual Dimensions of Nursing Practice. Philadelphia: Templeton Press (edited by Verna Benner Carson and Harold G. Koenig – click here for an excerpt

This chapter uses a public health perspective to describe a successful collaboration between the Health Association of Niagara County, Inc. (HANCI), the Niagara County Office for the Aging, the Niagara County Health Department, the Mental Health Association, the Coalition of Agencies in Service to the Elderly (CASE) and an interfaith collaborative that launched an Aging Well program (originally published as “What I Wish I Knew” and now available as “Caregiver Stories and Stress Solutions

between the Health Association of Niagara County, Inc. (HANCI), the Niagara County Office for the Aging, the Niagara County Health Department, the Mental Health Association, the Coalition of Agencies in Service to the Elderly (CASE) and an interfaith collaborative that launched an Aging Well program (originally published as “What I Wish I Knew” and now available as “Caregiver Stories and Stress Solutions

It was f

It is based on these concepts;

- Emotional and spiritual health can grow despite physical decline

- Love is common to all religions.

- Love is an important value for all family, organizational and community issues.

- The same two processes (The Satisfaction Skills and the Learning Poem) can help well seniors, the elderly, caregivers and organization

This program – funded by grants from the Niagara County Office for the Aging; the CommunityHealth Foundation of Central and Western New York and the Ralph Wilson Foundation.was honored by AARP’s Social Impact Award as “a simple mind-body-spirit program for seniors, adults and teens of any faith, or no faith.”

DeLoughry, T. Spirituality and Health Status (unpublished study)

This survey of 169 member of three different churches was supported by the Niagara County Office for the Aging. It was designed to assess the following factors in faith-based and other communities:

- Health status (using a Center for Disease Control questions for physical and emotional health) Spiritual practices and well-being (show in red below)

- Volunteerism

- Behaviors associated with decreased hospitalization.

- Use of four communication, stress management and prayer skills (i.e., awareness, affirmations, assertiveness, acceptance – which are taught as the “Satisfaction Skills”)

Our ongoing studies that have documented that emotional health is significantly affected by prayer and forgiveness (as illustrated below). That is , those who are able to forgive themselves and others, as well as those who often pray privately, have significantly fewer “bad emotional days” each month.

Our research has also found a strong association (R2 = 52 – using stepwise multiple regression) between spiritual wellness and the following factors:

- Looking to God for guidance

- Ability to forgive myself (acceptance)

- Carrying religious beliefs into all areas of life

- Praying privately

- Telling thoughts and feelings to others (assertiveness)

Farida K. Ejaz, PhD, Linda S. Noelker, PhD, Heather L. Menne, PhD, Joshua G. Bagaka’s, PhD, The Impact of Stress and Support on Direct Care Workers’ Job Satisfaction, The Gerontologist, Volume 48, Issue suppl_1, July 2008, Pages 60–70

This research applies a stress and support conceptual model to investigate the effects of background characteristics, personal and job-related stressors, and workplace support on direct care workers’ (DCW) job satisfaction.

Researchers collected survey data from 644 DCWs in 49 long-term care (LTC) organizations. The DCWs included nurse assistants in nursing homes, resident assistants in assisted living facilities, and home care aides in home health agencies. We examined the influence of components of the LTC stress and support model on DCW job satisfaction.

Results: Components of the model explained 51% of the variance in DCW job satisfaction. Background characteristics of DCWs were less important than personal stressors (e.g., depression), job-related stressors (e.g., continuing education), and social support (e.g., interactions with others) in predicting job satisfaction. Results from hierarchical linear modeling analysis showed that nursing homes compared to the two other types of LTC organizations had lower average DCW job satisfaction rates, as did organizations offering lower minimum hourly rates and those reporting turnover problems.

Dharmawardene, M., Givens, J., Wachholtz, A., Makowski, S., & Tjia, J. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of meditative interventions for informal caregivers and health professionals. BMJ supportive & palliative care, 6(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000819

Burnout, stress and anxiety have been identified as areas of concern for informal caregivers and health professionals, particularly in the palliative setting. Meditative interventions are gaining acceptance as tools to improve well-being in a variety of clinical contexts, however, their effectiveness as an intervention for caregivers remains unknown.To explore the effect of meditative interventions on physical and emotional markers of well-being as well as job satisfaction and burnout among informal caregivers and health professionals.

Systematic review of randomised clinical trials and pre–post intervention studies with meditative interventions for caregivers.68 studies were examined in full text with 27 eligible for systematic review. Controlled trials of informal caregivers showed statistically significant improvement in depression (effect size 0.49 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.75)), anxiety (effect size 0.53 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.99)), stress (effect size 0.49 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.77)) and self-efficacy (effect size 0.86 (95% CI 0.5 to 1.23)), at an average of 8 weeks following intervention initiation. Controlled trials of health professionals showed improved emotional exhaustion (effect size 0.37 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.70)), personal accomplishment (effect size 1.18 (95% CI 0.10 to 2.25)) and life satisfaction (effect size 0.48 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.81)) at an average of 8 weeks following intervention initiation.

Meditation provides a small to moderate benefit for informal caregivers and health professionals for stress reduction, but more research is required to establish effects on burnout and caregiver burden.

Gilhooly, K. J., Gilhooly, M. L., Sullivan, M. P., McIntyre, A., Wilson, L., Harding, E., Woodbridge, R., & Crutch, S. (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC geriatrics, 16, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8

There has been a substantial number of systematic reviews of stress, coping and interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. This paper provides a meta-review of this literature 1988-2014.

The meta-review identified 45 systematic reviews, of which 15 were meta-analyses. Thirty one reviews addressed the effects of interventions and 14 addressed the results of correlational studies of factors associated with stress and coping. Of the 31 systematic reviews dealing with intervention studies, 22 focused on caregivers, 6 focused on people with dementia and 3 addressed both groups. Overall, benefits in terms of psychological measures of mental health and depression were generally found for the use of problem focused coping strategies and acceptance and social-emotional support coping strategies. Poor outcomes were associated with wishful thinking, denial, and avoidance coping strategies. The interventions addressed in the systematic reviews were extremely varied and encompassed Psychosocial, Psychoeducational, Technical, Therapy, Support Groups and Multicomponent interventions. Specific outcome measures used in the primary sources covered by the systematic reviews were also extremely varied but could be grouped into three dimensions, viz., a broad dimension of “Psychological Well-Being v. Psychological Morbidity” and two narrower dimensions of “Knowledge and Coping” and of “Institutionalisation Delay”.

This meta-review supports the conclusion that being a caregiver for people with dementia is associated with psychological stress and physical ill-health. Benefits in terms of mental health and depression were generally found for caregiver coping strategies involving problem focus, acceptance and social-emotional support. Negative outcomes for caregivers were associated with wishful thinking, denial and avoidance coping strategies. Psychosocial and Psychoeducational interventions were beneficial for caregivers and for people with dementia. Support groups, Multicomponent interventions and Joint Engagements by both caregivers and people with dementia were generally found to be beneficial. It was notable that virtually all reviews addressed very general coping strategies for stress broadly considered, rather than in terms of specific remedies for specific sources of stress. Investigation of specific stressors and remedies would seem to be a useful area for future research.

Caudill, M. E. and M. Patrick (1991). “Turnover among nursing assistants: why they leave and why they stay.” J Long Term Care Adm 19(4): 29-32.

Overall, the data from the study show that nursing assistants who were planning to leave their present employment within the next three months were younger, had been in their positions less time, were paid less, and were better educated than those who were planning to stay in their present jobs. Also, the assistants who were planning to leave were not planning to stay in nursing as a life’s career. They were planning to leave their present jobs because they had less input into the planning of care and conferences on care, attended fewer in-service programs, and ranked their own nursing skills lower than their peers. Changing patient assignments on a daily basis was more often associated with plans to leave than was changing patient assignments weekly or never. Finally, nursing assistants who were planning to leave cared for more patients per shift than those who were planning to stay. Nursing assistants who were planning to leave their jobs imminently had been employed for 12 or fewer months more frequently than nursing assistants who were planning to stay. The leavers were also in their first nursing job more frequently than the latter group and seemed to be a more critical group as well: 27% of those who were leaving reported that they criticized the policy or procedure of their facility sometimes or even frequently, a higher percentage than almost any other variable tested in the study. Another variable that was different between the two groups was what they considered most important to them.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Cohen-Mansfield, J. (1997). “Turnover among nursing home staff. A review.” Nurs Manage 28(5): 59-62, 64.

Turnover is especially critical in nursing homes: continuity of care and personal relationships between care-givers and residents are important determinants of quality of care. Additionally, for the cognitively impaired nursing home resident, constant change of staff is bound to aggravate disorientation. Research demonstrates links between turnover and employment/employee characteristics and employment availability.

Davidson, H., P. H. Folcarelli, et al. (1997). “The effects of health care reforms on job satisfaction and voluntary turnover among hospital-based nurses.” Med Care 35(6): 634-45.

OBJECTIVES: Among the consequences of downsizing and cost containment in hospitals are major changes in the work life of nurses. As hospitals become smaller, patient acuity rises, and the job of nursing becomes more technical and difficult. This article examines the effects of changes in the hospital environment on nurses’ job satisfaction and voluntary turnover between 1993 and 1994. METHODS: Data were collected in a longitudinal survey of 736 hospital nurses in one hospital to examine correlates of change in aspects of job satisfaction and predictors of leaving among nurses who terminated in that period. RESULTS: Unadjusted results showed decline in most aspects of satisfaction as measured by Hinshaw and Atwood’s and Price and Mueller’s scales. Multivariate analysis indicated that the most important determinants of low satisfaction were poor instrumental communication within the organization and too great a workload. Intent to leave was predicted by the perception of little promotional opportunity, high routinization, low decision latitude, and poor communication. Predictors of turnover were fewer years on the job, expressed intent to leave, and not enough time to do the job well. CONCLUSIONS: The authors conclude that although many aspects of job satisfaction are diminished, some factors predicting low satisfaction and turnover may be amenable to change by hospital administrators.

Davis, D. A., M. A. Thomson, et al. (1995). “Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies [see comments].” Jama 274(9): 700-5.

OBJECTIVE–To review the literature relating to the effectiveness of education strategies designed to change physician performance and health care outcomes. DATA SOURCES–We searched MEDLINE, ERIC, NTIS, the Research and Development Resource Base in Continuing Medical Education, and other relevant data sources from 1975 to 1994, using continuing medical education (CME) and related terms as keywords. We manually searched journals and the bibliographies of other review articles and called on the opinions of recognized experts. STUDY SELECTION–We reviewed studies that met the following criteria: randomized controlled trials of education strategies or interventions that objectively assessed physician performance and/or health care. CME delivery methods such as conferences have little direct impact on improving professional practice. More effective methods such as systematic practice-based interventions and outreach visits are seldom used by CME providers.

Dunphy, K. F., & Hens, T. (2018). Outcome-Focused Dance Movement Therapy Assessment Enhanced by iPad App MARA. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2067. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02067

Healthcare and human services are increasingly required to demonstrate effectiveness and efficiency of their programs, with assessment and evaluation processes more regularly part of activity cycles. New approaches to service delivery, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) scheme in Australia, require outcome-focused reporting that is responsive to the perspectives of clients. Eco-systematic approaches to service delivery and assessment consider the client as part of an interconnected web of stakeholders who all have responsibility for and contribute to their development and progress. These imperatives provide challenges for modalities for which there are not well-established assessment approaches.

Roth, David L., Lisa Fredman, and William E. Haley. “Informal Caregiving and Its Impact on Health: A Re`appraisal from Population-Based Studies.” The Gerontologist 55, no. 2 (April 2015): 309–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu177.

Adams, C. E. and M. Wilson (1995). “Enhanced quality through outcome-focused standardized care plans.” J Nurs Adm 25(9): 27-34.

Methods to improve the quality of care are a national issue for home healthcare agencies. In comparison with the traditional process- focused care plans, outcome-focused care plans (OCPs) resulted in significantly better quality indicator scores for clients cared for by agency staff members. Although OCPs are a valuable tool for enhancing quality, tools are only as good as the individuals who use them. Before deciding to change to an OCP format, administrators must assess all resources needed to effect the change.

Gaddy, T. and G. A. Bechtel (1995). “Nonlicensed employee turnover in a long-term care facility.” Health Care Superv 13(4): 54-60.

The purpose of this study was to analyze nonlicensed employee turnover in a long-term care facility using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a framework. During exit interviews, a convenience sample of 34 employees completed an attitudes and beliefs survey regarding their work environment. Findings were mixed; 39.6 percent of the employees stated positive personal relationships were a strength of the organization, although 24.3 percent resigned because of personal/staff conflicts. Financial concerns were not a major factor in their resignations. The study suggests that decreasing nonlicensed employee stress and increasing their personal satisfaction with patient care may decrease employee turnover.

Helmer, F. T., S. F. Olson, et al. (1993). “Strategies for nurse aide job satisfaction.” J Long Term Care Adm 21(2): 10-4.

With average turnover costs equaling four times an employee’s salary, administrators cannot afford to lose nurse aides. This study explored why aides leave and ways to improve your facility’s work environment.

Li, Y., Li, J., Zhang, Y., Ding, Y., & Hu, X. (2022). The effectiveness of e-Health interventions on caregiver burden, depression, and quality of life in informal caregivers of patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International journal of nursing studies, 127, 104179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104179

With the increasing incidence and survival rate of cancer, there are more people living with cancer, which increases the responsibilities of informal caregivers and results in a significant caregiver burden, depression, and low quality of life. The efficacy of e-Health interventions has already been proven in decreasing caregiver burden, addressing psychosocial concerns, and increasing quality of life among caregivers of patients with chronic diseases. However, the utilization of e-Health interventions on the informal caregivers of cancer patients is still limited and the effectiveness is unclear.

To assess the impact of e-Health interventions on the caregiver burden, depression, and quality of life of informal caregivers of cancer patients.

Seven randomized controlled trials with 326 participants were included in the review. The results of the meta-analysis showed that e-Health interventions could significantly improve the depression (SMD = -0.90, 95% CI [-1.76∼-0.04], P = 0.04) and quality of life (SMD = 0.45, 95% CI [0.13∼0.77], P = 0.006), but not caregiver burden (SMD = -0.29, 95% CI [−0.61∼0.02], P = 0.07) in informal caregivers. Sensitivity analysis showed that only the caregiver burden was stable.

e-Health interventions are a convenient method to support the informal caregivers of cancer patients, and can mitigate depression and enhance the quality of life of informal caregivers, but had no significant effect on easing the caregiver burden. In future, tailored e-Health intervention, based on informal caregivers’ demographic characteristics and cultural context, is warranted to improve informal caregivers’ well-being.

Mathews, J. J. and C. Nunley (1992). “Rejuvenating orientation to increase nurse satisfaction and retention.” J Nurs Staff Dev 8(4): 159-64.

The current nursing shortage has forced nursing managers to examine the reasons for nurse turnover and to evaluate institutional programs and policies that may strengthen staff nurse retention. For the past two decades, the nursing profession has concluded that nurse retention is linked to job satisfaction. Accordingly, employers have attempted to improve job satisfaction by permitting self-scheduling, nurse selection of unit assignment, and bonus pay for less desirable shifts. In spite of these and other efforts designed to retain nurses, the turnover rate generally has remained high.

Mesirow, K. M., A. Klopp, et al. (1998). “Improving certified nurse aide retention. A long-term care management challenge.” J Nurs Adm 28(3): 56-61.

In the long-term care industry, the turnover rate among nurse aides is extremely high. This adversely affects resident satisfaction, resident care, morale, and finances. It presents a challenge to long-term care administration. Refusing to accept high turnover as an impossible situation allows changes to be made. The authors describe how the staff at one intermediate care facility identified its problems, assessed the causes, and implemented corrective action.

Prevosto, P. (2001). “The effect of “mentored” relationships on satisfaction and intent to stay of company-grade U.S. Army Reserve nurses.” Mil Med 166(1): 21-6.

This study examined the strategic implications of mentoring relationships perceived by company-grade U.S. Army Reserve nurses. The effects of mentorship on professional socialization, job satisfaction, and intent to stay were examined using the adapted framework of Hunt and Michael. The study population consisted of U.S. Army Reserve nurses from all three components of the ready reserve. One hundred nurses from each category were randomly selected and provided a questionnaire. The questionnaire combined Dreher’s Mentoring Scale, Price’s Intent-to-Stay Scale, and Hoppock’s Job Satisfaction Scale. The overall response rate was 57%. Seventy-two of the 171 respondents reported at least one mentored experience. Findings indicate that mentored nurses report more satisfaction and have a higher intent to stay than nonmentored nurses. Continued research and encouragement of mentoring are recommended.

Proenca, E. J. and R. M. Shewchuk (1997). “Organizational tenure and the perceived importance of retention factors in nursing homes.” Health Care Manage Rev 22(2): 65-73.

Health care organizations can avoid substantial turnover costs through retention strategies geared to the varying needs of employees. The study on which this article is based examined retention needs of registered nurses in nursing homes and found that they varied by tenure. Low tenure nurses preferred learning opportunities and advancement potential while high tenure nurses favored work flexibility. Implications for retention policy in nursing homes are discussed.

Shader, K., M. E. Broome, et al. (2001). “Factors influencing satisfaction and anticipated turnover for nurses in an academic medical center.” J Nurs Adm 31(4): 210-6.

OBJECTIVES: The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between work satisfaction, stress, age, cohesion, work schedule, and anticipated turnover in an academic medical center. BACKGROUND DATA: Nurse turnover is a costly problem that will continue as healthcare faces the impending nursing shortage, a new generation of nurses enter the workforce, and incentives provided to nurses to work for institutions increase. A variety of factors influence the retention of nurses in adult care settings, including work satisfaction, group cohesion, job stress, and work schedule. In general, previous research has documented positive relationships between work satisfaction, group cohesion, strong leadership, and retention rates and a negative relationship between stress, work schedule, and retention. In addition, age and experience in nursing are related to job satisfaction. METHODS: This study used a cross-sectional survey design in which nurses from 12 units in a 908-bed university hospital in the Southeast completed questionnaires on one occasion. The following factors were measured using self-report questionnaires: nurse perception of job stress, work satisfaction, group cohesion, and anticipated turnover. RESULTS: The more job stress, the lower group cohesion, the lower work satisfaction, and the higher the anticipated turnover. The higher the work satisfaction, the higher group cohesion and the lower anticipated turnover. The more stable the work schedule, the less work-related stress, the lower anticipated turnover, the higher group cohesion, and the higher work satisfaction. Job Stress, work satisfaction, group cohesion, and weekend overtime were all predictors of anticipated turnover. There are differences in the factors predicting anticipated turnover for different age groups. CONCLUSIONS: As healthcare institutions face a nursing shortage and a new generation of nurses enter the workforce, consideration of the factors that influence turnover is essential to creating a working environment that retains the nurse.

Song, R., B. J. Daly, et al. (1997). “Nurses’ job satisfaction, absenteeism, and turnover after implementing a special care unit practice model.” Res Nurs Health 20(5): 443-52.

The purpose of the study was to compare job satisfaction, absenteeism, and turnover between nurses working in a nurse-managed special care unit (SCU) and those working in traditional intensive care units (ICU). A case management practice model with a shared governance management model and minimal technology was implemented in the SCU while contrasting features of a primary nursing practice model with a bureaucratic management model and high technology already in place in the traditional ICU. Individual nurses’ perceptions of and their preferences for the SCU practice model also were examined related to job satisfaction. Using analysis of covariance, greater satisfaction with a lower absenteeism rate was found in nurses working in the SCU. Nurses’ perceptions and preferences for the SCU practice model were closely related to their job satisfaction and growth satisfaction. The findings suggest that individual perception and preference should be taken into account before implementing autonomy, authority, and responsibility at the organizational level to lead to the desired nurse outcomes in a given working environment.

van Wijk, C. (1997). “Factors influencing burnout and job stress among military nurses.” Mil Med 162(10): 707-10.

Burnout among military nurses has been found to lead to job absenteeism, staff conflicts, and a high turnover of personnel. Factors influencing nurses working in smaller and often isolated military installations of the South African National Defence Force were investigated using a job-stress and burnout questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. Investigation focused on registration categories, geographic location, and age. It was found that the senior registration categories experienced more burnout, and nurses in isolated areas reported almost double the number of cases of burnout than nurses in larger centers. Age played a role in the very young (19-25 years) and older (40-50 years) nurses. The lack of support from supervisors, high responsibility, long working hours, and task overload were the four most common stressors reported. Some suggestions are forwarded to manage the risk of burnout among military nurses in similar situations.

HOME HEALTH AIDES

Buelow, J. R., K. Winburn, et al. (1999). “Job satisfaction of home care assistants related to managerial practices.” Home Health Care Serv Q 17(4): 59-71.

This article addresses the question. “How do specific managerial practices support home care assistants’ job satisfaction?” Staff from three home care agencies were surveyed regarding their perceptions of specific managerial practices and intrinsic job satisfaction. Results of a hierarchical regression model indicate that supportive leadership practices, client-centered in-service training style, and mission implementation together explained 52% of the variance in intrinsic job satisfaction. Supportive leadership was described as the extent to which a supervisor communicates effectively, shows personal concern or caring, and maintains high professional standards. Mission implementation was defined as how strongly the staff felt the mission influenced the hiring process, orientation, in-services, and everyday management. Effective in-services included discussions of types of clients and how to effectively handle common challenges.

Dutcher, L. A. and C. E. Adams (1994). “Work environment perceptions of staff nurses and aides in home health agencies.” J Nurs Adm 24(10): 24-30.

Nurse executives are responsible for ensuring a therapeutic work environment in their organizations. Understanding how staff members perceive their environment is the first step in creating such an environment. In this study, perceptions of the work environment between staff nurses and home health aides in home health agencies were compared. The results suggest that nurse executives need to foster home health aides’ job commitment and support for one another and increase opportunities for staff nurses to be innovative and autonomous in their practice.

Guariglia, W. (1996). “Sensitizing home care aides to the needs of the elderly.” Home Healthc Nurse 14(8): 618-23.

Creative teaching strategies can be used to teach all home care providers how to empathize with their elderly patients. This article describes a simulation exercise used successfully by one educator to allow home care aide students to experience the limitations of aging and to better understand the situations of their patients.

Najera, L. K. and B. A. Heavey (1997). “Nursing strategies for preventing home health aide abuse.” Home Healthc Nurse 15(11): 758-67; quiz 769-70.

One of home care’s most important resources is the home health aide. Home care nurses play a critical role in preventing abuse of home health aides and identifying violence-prone environments. A prevention strategy that nurses can use to identify and prevent abuse of both patients and aides is presented using an Assessment, Communication, Education, and Supervision model.

Richman, F. (1997). “Home care aides and the business of people.” Caring 16(4): 62-3.

A home care aide (HCA) needs both patient care skills and people skills to do the job well. Recruiting HCAs with those skills can assist in HCA retention while improving customer service.

Richman, F. (1998). “The entrepreneurial spirit and home care aides.” Caring 17(4): 56-7.

Emphasis in the home care industry is being placed on the development of private services in home care. Traditional management characteristics are necessary for this, but so are entrepreneurial ways of thinking–and those may come from all levels of an organization, even and especially home care aides.

Rosengarten, L., F. Milburn, et al. (1996). “Helping home care aides work with newly dependent elderly in a cluster care setting.” Home Healthc Nurse 14(8): 638-46.

A Cluster Care Aide Model of home care was implemented within a senior apartment complex in New York City. Many unforeseen difficulties arose when traditional home health aides were teamed with newly dependent elderly. Cooperation between the administrators of the two agencies created a specialized orientation and in-service program with positive outcomes.

Royse, D., S. Dhooper, et al. (1988). “Job satisfaction among home health aides.” Home Health Care Serv Q 9(1): 77-84.

This study reports on job satisfaction from a survey of 132 home health aides using Locke’s Action Tendency Interview Schedule. The major findings were that respondents who had been employed in home health care for five years or less were more satisfied than those who had been working in the area for a longer period and that there were no differences in job satisfaction by age.

Schmidt, K. and E. Kennedy (1998). “Reduce home care aide turnover: give aides real jobs.” Caring 17(8): 56-7.

What do home care aides want even more than a raise? Consistent, full-time work hours. That’s what one agency found out in its attempt to decrease employee turnover. There are other steps agencies can take, too, to keep their aides coming back.

Surpin, R., K. Haslanger, et al. (1994). “Better jobs, better care: building the home care work force.” Pap Ser United Hosp Fund N Y: 1-54.

This paper focuses on providing quality care in the paraprofessional home care industry. Despite government policies that have encouraged home-based care for 20 years, home health care still remains relegated to second-class status by the rest of the health care industry. Home care is unique because it relies primarily on paraprofessional care delivered by a home care aide working alone, essentially as a guest in the client’s home. The resulting interpersonal dynamic between patient and caregiver–which develops far from the eyes of the primary physician, regulators, and third-party payers–is one unlike any other patient-caregiver relationship in the health care system. The quality of care received by the client is linked directly to the quality of the paraprofessional’s job: “good jobs” are prerequisite for “good service.” Good jobs, however, are not enough. They must be supported by paraprofessional agencies that add real value to the home care service. Part I We define quality home care as meeting the client’s needs. Unfortunately, since home care is provided in dispersed, minimally supervised settings, measuring quality of service is very difficult. For this reason, we suggest that it is the front-line employee–the home care aide who is present for hours every visit–who can best determine if the client’s needs are being met, and who is best positioned to respond accordingly. Part II To best meet client needs, paraprofessional home care must be built around the home care aide. This requires that home care aides (1) be carefully selected during the hiring process, (2) be well trained, and (3) be empowered with considerable responsibility and capacity to respond to the daily needs of the clients. This Model, one that emphasizes the front-line employee, is in full keeping with the “total quality management” innovations that are currently reorganizing America’s service industries. Unfortunately this model is not typically reflected in current paraprofessional home health care practice. Part III Building the home care service around home care aide requires redesigning the paraprofessinal’s job in 5 ways: 1. Make work pay, by providing a minimum of $7.50 per hour and a decent benefits package.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Walter, B. M. (1996). “Home care aide retention: building team spirit to avoid employee walkouts.” Home Healthc Nurse 14(8): 609-13.

While home care agencies work to increase productivity and decrease costs, it is easy to lose sight of the value of employees. Because home care aides are seldom in the office, their value to the organization may get overlooked. In this article, one home care agency shares ways to build team spirit among the home care aides and empower them to be better employees. The result has been increased productivity, improved morale, and a more stable workforce.

Wilner, M. A. (1999). “Recruiting qualified home care aides: new candidate pools.” Caring 18(4): 44-5.

With the demographic surge of baby boomers and the number of women aged 25-45 projected to decline, the coming decades will see a shortage of workers to care for the elderly. Home care aide agencies will only be able to retain their competitive edge if they widen the pool of candidates from which they recruit and create an attractive and decent job. Creating a decent job with adequate pay, benefits, and support is a business strategy that will attract a wider range of workers, including those with minimal experience, and have positive ramifications for health care in the future–and now.