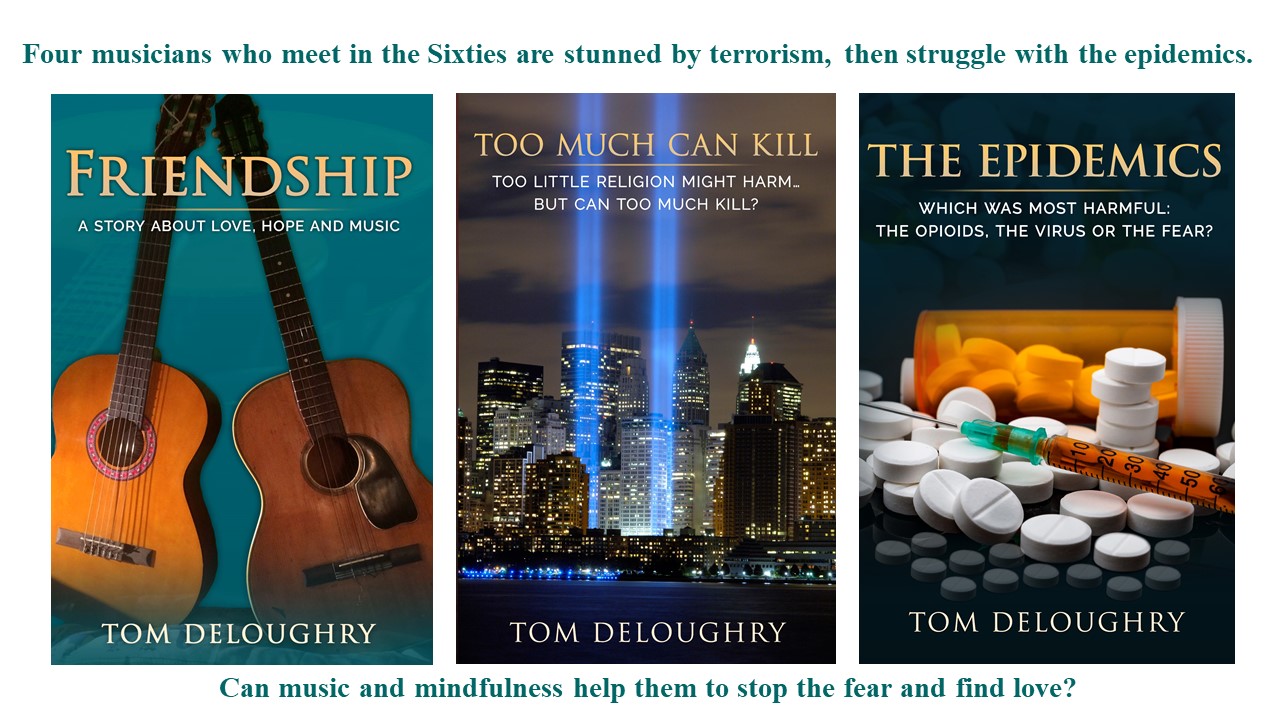

Art, such as drawings, paintings and sculpture, is used throughout the Friendship Trilogy to provoke mv characters, foreshadow emotions, and reveal their changing perspectives over time.

As the story opens, Susan, an unhappy homecoming queen who is disliked by nearly everyone, is offended by a drawing she sees while out drinking with a friend during Spring Break in the Bahamas.

As we were crossing one of the bigger streets, I saw a man on the corner passing out flyers. He was old, maybe in his forties, but very fit with ruddy skin and a great head of sandy hair.

I took a flyer to be polite, glancing at the big bold letters that said: “FREE: See the Real Bahamas.” But the graphic at the bottom of the page caught my eye, and I stopped to examine it under the next streetlight.

The drawing featured a clenched fist, like the black power symbol that made me a little nervous at some of the anti-war demonstrations. But this fist was inside the well-known symbol for Venus or the feminine: a round circle with a cross dangling below it. The fist was drawn so that its wrist and the forearm became the upright part of the cross.

I was offended and, then, intrigued.

I walked back to the corner where he stood under a street light and asked, “So, what are the real Bahamas?”

“My wife and I are offering a free tour tomorrow so anyone who is interested can see for themselves,” he said. “We can pick you up at noon, show you our mission school, see a couple of the sights, and get you back to your hotel by sunset. Interested?”

After Susan meets Donna on the tour the next day (just hours before Martin Luther King is killed) they view a more vivid full-color version of the logo on the side of the mission bus. Both Susan and Donna are appalled by the bloody thorns on the cross, but begin to rethink the power of women.

Before the tour ends, they stop at Clifton Pier where they view the rubble of a slave prison and a stone pier where thousands of Africans first landed in the New World.

Susan narrates: We followed Melanie up a sandy path to the tip of the peninsula. Near the edge of the cliff a thin African woman wearing robes and a headdress leaned mournfully towards the sea …towards her home.

As we got closer I realized it wasn’t a woman. It was a heartbreaking sculpture carved from a tree trunk that was still rooted to the ground. A woman who could never return home, no matter how hard she yearned.

“This was created by Antonius Roberts, the son of a good friend,” Melanie said. “He’s barely a teen, yet he is an old soul. He said he hopes that someday this will be a sacred space with dozens of spirits, each remembering her past, while rooted in the present and hoping for the future.”

We stared at the carving, its dignity and its grace. Its pain.

“Can you imagine?” Melanie said softly, looking back at the ruins. “They each had friends and families, just like us. But they were captured like animals and thrown into the bellies of the slave ships. Stacked like wood in shelves that were two feet high. Over eleven million people. They could never go home.”

I knew about slavery as words in a textbook. Now I felt fear in my stomach and an ache in my heart. People did this to other people?

“Husbands were separated from their wives and mothers from their children,” she paused. “Any man who objected was whipped – or worse. The prettiest girls were raped,” she said looking at Donna and me. “Over and over again.”

My skin crawled as I tried not to imagine it.

“It happened every day. Every day to thousands of people for nearly one hundred years,” she said looking toward the ruins.

Tears were streaming down Donna’s face, her hands clenched at her side, as she faced John and Melanie. “So where was your God when all of that was happening?” She took a deep breath to stop an angry sob. “When women were being raped and their children were taken away from them?”

Donna turned away and faced the sea, as graceful and sad as the woman the boy had carved.

This scene foreshadows two of Donna’s secrets: she had been raped when she was 15 and then forced to give up her baby. The reader learns this in the next chapter but, despite their strong friendship, Donna doesn’t tell Susan for six more years.

SPOILER ALERT – The rest of this summary is intended for agents, publishers and critics. If you plan to read this novel for entertainment, it will give away some of the plot.

***

After Donna decides to become a celibate Methodist minister to fight the church’s discrimination against homosexuals from the inside, her first ministry is rocked when a teen-age boy falls off the ledge of a burning home and is paralyzed from the waist down. Donna nearly loses her job because, rather than pray for a miracle so Mike would walk again, she instead opts to teach him to find the satisfaction of everyday miracles that are always in the present moment. After an avalanche of initial anger, the progress of Mike’s healing is evidenced, first, by a graphic that illustrates the love that is always waiting for us now (see illustration) and, later, by series of abstract paintings.

After Donna decides to become a celibate Methodist minister to fight the church’s discrimination against homosexuals from the inside, her first ministry is rocked when a teen-age boy falls off the ledge of a burning home and is paralyzed from the waist down. Donna nearly loses her job because, rather than pray for a miracle so Mike would walk again, she instead opts to teach him to find the satisfaction of everyday miracles that are always in the present moment. After an avalanche of initial anger, the progress of Mike’s healing is evidenced, first, by a graphic that illustrates the love that is always waiting for us now (see illustration) and, later, by series of abstract paintings.

And, finally, art is used to communicate hope, and reveal how the characters change over time

Throughout the book, Donna’s paintings of a New England seaside town is used to:

- create hope – as Donna, isolated and pregnant in Buffalo, imagines a happy life for her and her baby

- communicate love – midway through the novel, Donna shows that painting to her son as a way of telling him she always loved him – although she was forced to give him up for adoption

- foreshadow the happiness of her granddaughter, Alice, as described in the following scene:

After Donna dies at the World Trade Center, she visits her granddaughter, Alice, now twelve [who the reader first meets when she is a twenty-seven-year-old woman substituting for her grandmother at Friendships’s 2016 September 11th Memorial Concert]. The twelve-year-old Alice is sketching a new version of that seaside town. As Donna watches, she is assured that Alice will always feel her father’s love.

Donna narrates this after her death:

I rose up over the North Tower, looking down, a mushroom of smoke rising toward me, papers, dust clouds, racing up every city street.

Countless glows rising with me, spreading instantly through the city and beyond. Not to say good-bye, but hello.

In Yonkers, Joey was stretched out on the family room rug, playing with his trains. When he sensed me, he smiled at the sunbeam over his shoulder and crawled into its warmth, pulling his trains with him.

Upstairs, Alice, now twelve, was using her Jon Nagy kit to sketch a father and child in a New England fishing village. When I painted that scene at 16, during that hot, humiliating summer when I was waiting for my son to be born, I saw the town from the sea. It was a pretty haven where the buildings were colorful smudges and the people were featureless specks. A place where my baby and I could live in love.

In hers, she looked out to sea. The harbor and the tiny boats were down the hill, the sunrise mirrored pink and crimson in the sea. A father and his little girl were in the foreground, laughing as they smelled a wildflower bouquet, still shiny with dew. The father had Barry’s smile and the soft glow of his eyes, like the old picture that I took when he and his friends were recording in my little studio.

As I watched, Alice erased and redrew the father’s hand. Now it gently touched the girl’s chubby forearm, supporting her as she looked up, a giggle brightening her face. Alice was too young to remember much about her father, but she would always know how his love felt.